-

What skyrocketing tomato prices tell us about corn

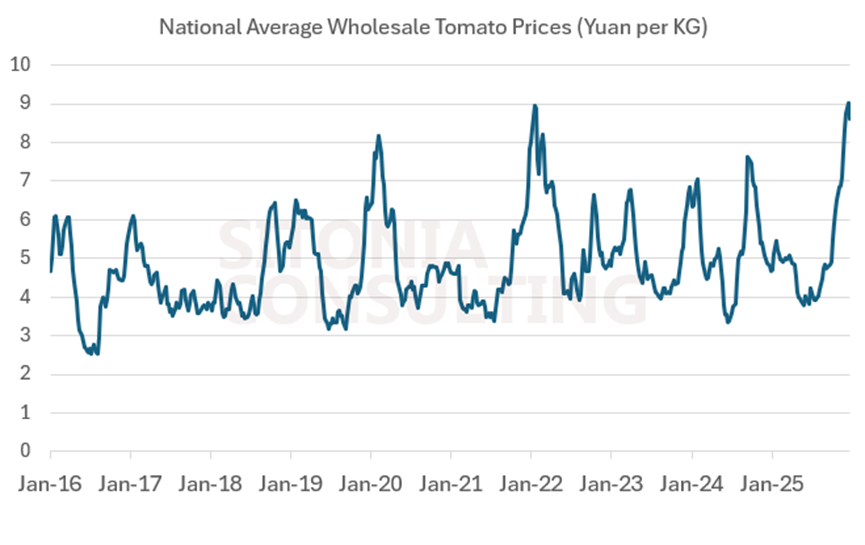

National average wholesale tomato prices hit 9.02 yuan per KG at the beginning of January, according to market monitoring from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. This is the highest on record, going back at least 10 years.

Prices are up 80% year on year, and up 120% since the beginning of August.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, prices in December 2024 were 7% lower than the seasonal average, and good weather conditions in the first half of 2025 led to increased production and lower prices. This led some farmers to reduce their planting, but there was also heavy rainfall in the autumn in major tomato-producing areas. This reduction in planting, along with adverse weather, led to the current price spike.

As reported last week, December CPI rose 0.8% year on year, the highest in nearly two years. Vegetable prices were up 18.2% year on year, which contributed an increase of 0.39 percentage points to the index. In comparison, pork price fell 14.6%, which contributed a decline of 0.20 percentage points.

Shandong province is the largest producer of tomatoes, and neighboring Henan and Hebei are also large producers.

These three provinces also account for 26% of China’s corn production. The same excessive rains that led to a reduction in tomato output also affected corn that was close to harvest. However, the National Bureau of Statistics still reported that grain production in these provinces increased year on year, and that China had a record corn crop in 2025.

Fruits and vegetables are perishable products that can’t be stockpiled. Because of this, China sees more volatility in the prices of these commodities. The price spikes in fruits and vegetables tend to be short-lived due to shorter growing cycles and more geographically diversified production, due to government policies that require a certain amount of a city’s vegetable demand to be grown locally.

The heavy rains during harvest caused issues for crops in northern China. In some cases, farmers were harvesting corn by hand in flooded fields, and there were subsequent problems with mold in the harvested corn. Similarly, vegetable farmers were dealing with flooded fields and structural damage to their greenhouses.

The impact of these heavy rains is now being reflected in vegetable prices, but it was not reflected in this year’s corn production statistics.

However, they are starting to be reflected in the corn market.

Last week, Sinograin auctioned around 400k tons of corn, with about 200k tons being imported corn, although these auctions are “invitation only”, so there is less transparency on the prices and volumes. Sinograin auctioned about 30k tons of corn in Jilin on Monday, which apparently fetched a premium.

Production in the northeast was higher this year and didn’t face the weather challenges seen in northern China.

In a recent report, Heilongjiang’s grain stockpiler notes that farmers in the province have sold over 50% of their grain, and this is a faster pace than last year. It also noted that feed companies are only buying what they need due to losses in the hog sector, and industrial processors have stockpiles significantly smaller than in previous years.

Heilongjiang is the largest corn producer in China and definitely saw increased production based on good growing conditions this year, and this is also supported by remote-sensing data.

Corn production in the province was higher, and farmers are reportedly selling faster than in previous years. This would mean a large amount of supply on the market.

At the same time, feed producers are only buying what they need because hog farms are losing money, and industrial processors aren’t stockpiling corn. The Ministry of Agriculture even noted the low corn inventory levels of industrial processors in its January China Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (CASDE) on Monday.

Larger supply and weak demand should mean lower prices, but over the past month, cash prices in Heilongjiang are up 20 yuan per ton.

One way to explain these contradicting data points is that a large amount of corn is flowing out of the northeast and to areas of northern China that were hit by the heavy rains at harvest. In that case, very expensive tomatoes are also telling us the quality or quantity of corn in northern China.

-

Estimating the yield loss for China’s very delayed wheat crop

Much of China’s winter wheat production was planted later than normal due to heavy rains which interfered with field work. Planting was delayed by around 20 days in Henan province, which alone accounts for 26% of national production. Delays were also seen in neighboring provinces of Shandong and Anhui, which account for 20% and 13% of production, respectively.

In 2020, a paper published in the European Journal of Agronomy specifically looked at yield losses due to late planting of winter wheat, in a corn-wheat rotation in Shaanxi province, which borders Henan to the west.

The study determined that wheat yields declined by 1% for each day that sowing was delayed outside the ideal window.

Due to the delayed sowing of winter wheat in 2025, the Ministry of Agriculture advised farmers to increase the seeding rate of winter wheat.

The 2020 paper examined this strategy. The results were that increasing the seeding rate completely offset the decline in yields for wheat planted with a one-week delay, and only partially offset the decline in yields for a two-week delay.

The authors write: “However, it should be noted that higher seeding rates could not compensate for the yield loss beyond a two-week delay in sowing.” The study was done over four growing seasons (2014-2018), and in the last two years of the study, the researchers also planted separate wheat plots with an increased seeding rate to measure the effectiveness of reducing yield loss despite late planting.

The researchers also looked at 9 other studies related to the delayed planting of winter wheat. Based on the results of those previous papers, they calculated losses of 0.7% for each day that wheat sowing was delayed.

(Yield penalty due to delayed sowing of winter wheat and the mitigatory role of increased seeding rate. Farooq Shah, Jeffrey A. Coulter, Cheng Ye, Wei Wu – European Journal of Agronomy, Volume 119, September 2020)

Quantifying delays

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, the optimal sowing period in Shandong province is October 5-15.

Shandong

This year, 20% was sown in Shandong before October 31. Another 55% was sown from November 1-10. There was 22% planted from November 11-20, and the remaining 3% was planted after November 21.

Being conservative and defining the last optimal planting date as being October 15, that puts 80% of Shandong wheat planting as over 2 weeks delayed.

Henan

For Henan province, the optimal sowing period is October 12-24. As of November 4, 29% of wheat was planted in Henan. From November 5-7, 19% was planted. From November 8-11, another 14% was planted. And from November 12-16, 29% was planted.

As of November 16, 91% of winter wheat was planted, meaning that the remaining 9% was planted after that date.

Being conservative and using the last optimal planting date, if 29% of the wheat area was planted by November 4, that means 71% of the crop was planted at least 11 days outside the ideal planting window.

The largest jump in planting progress was from November 12-16. On November 11, Henan reported 62% planted, and on November 16, they reported 91% planted. Using the latest date of the optimal planting window of October 24, that means 29% of the crop was planted 19-23 days late. Henan’s grain stockpiling agency also said planting was about 20-25 days late.

-

Beijing gets serious about reducing the hog herd

Yesterday, 25 large companies met with the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Agriculture in Beijing to discuss plans to reduce the size of the country’s hog industry.

The government reiterated that the sow population needs to be reduced by 1 million. The sow population has been relatively stable in recent months and was at 40.42 million in July.

Other reported measures seem much stricter.

This includes that provinces will also be responsible for reducing their respective sow herds as part of reaching the national goal of reducing the sow herd by 1 million.

This would be an important development because it shifts from more abstract guidance from the central government to a goal that the provincial officials are expected to achieve and enforce.

Large companies are expected to reduce their production by 10% in 2026. This is also something that has “teeth” from a regulatory perspective.

Before, sow reduction was a vague industry-wide target. Large companies could reduce their sow herds slightly to show they were trying to comply with the guidance and potentially focus on increasing their per sow yields.

But now, provincial level officials are being tasked with reducing the sow herd in their provinces, and companies are being told to cut their output in 2026.

Other actions to reduce production were also reiterated, such as limiting hog weights to 120kg and stopping the practice of secondary-fattening.

Lastly, the NDRC called on different financial regulators and local officials to control lending to hog companies, especially for anything related to capacity expansion. Local governments are also to reduce subsidies to hog producers.

This is a very dramatic policy reversal in a relatively short period of time. In less than five years, local governments have gone from saying things such as “efforts should be intensified to attract investment and support the construction of high-standard, modern, large-scale pig farms with a capacity of over 10,000 pigs” to now trying to limit hog production and prevent any increases in capacity. It also means a headwind for feed demand going into 2026. In 2024, hog feed accounted for 45% of animal feed

Latest reserach and analysis of agriculture market in China